Are we failing girls?

Girls out performing boys in both GCSE and A level in almost every subject. However, anyone who has taught in a single sex school will know that performance varies hugely across a single gender and this suggests that there is something more nuanced going on. Today’s blog summarises the research by Yu et al. (2020) that considers ‘Which Girls and Which Boys’ are underperforming.

Previous research has suggested that pupils who strongly conform to gender roles tend to have lower academic motivation, engagement and achievement. Masculinity can be reflected by emotional control competitiveness’, aggression, self-reliance and risk taking, whilst femininity can be reflected by thinness, appearance, orientation, romantic relationships and domestic duties. So both boys and girls who strongly adhere to these stereotypes do less well at school and are less motivated.

More girls adhere to these gender norms than boys, which suggests that the gender difference in academic performance may not be so clear cut.

How do these views of gender norms feed into academic motivation, engagement and achievement? At its most basic boys who hold a traditional view of masculinity ten to believe that ability is fixed and that if you try it indicates low ability and therefore they self-handicap by withholding effort, this also provides an excuse for failure despite the inconsistency in logic; they are also much less likely to ask for help. Girls who also hold traditional views about gender may believe they lack talent and so give up more easily – this seems particularly to happen after the transition into secondary school and may go unnoticed by teachers.

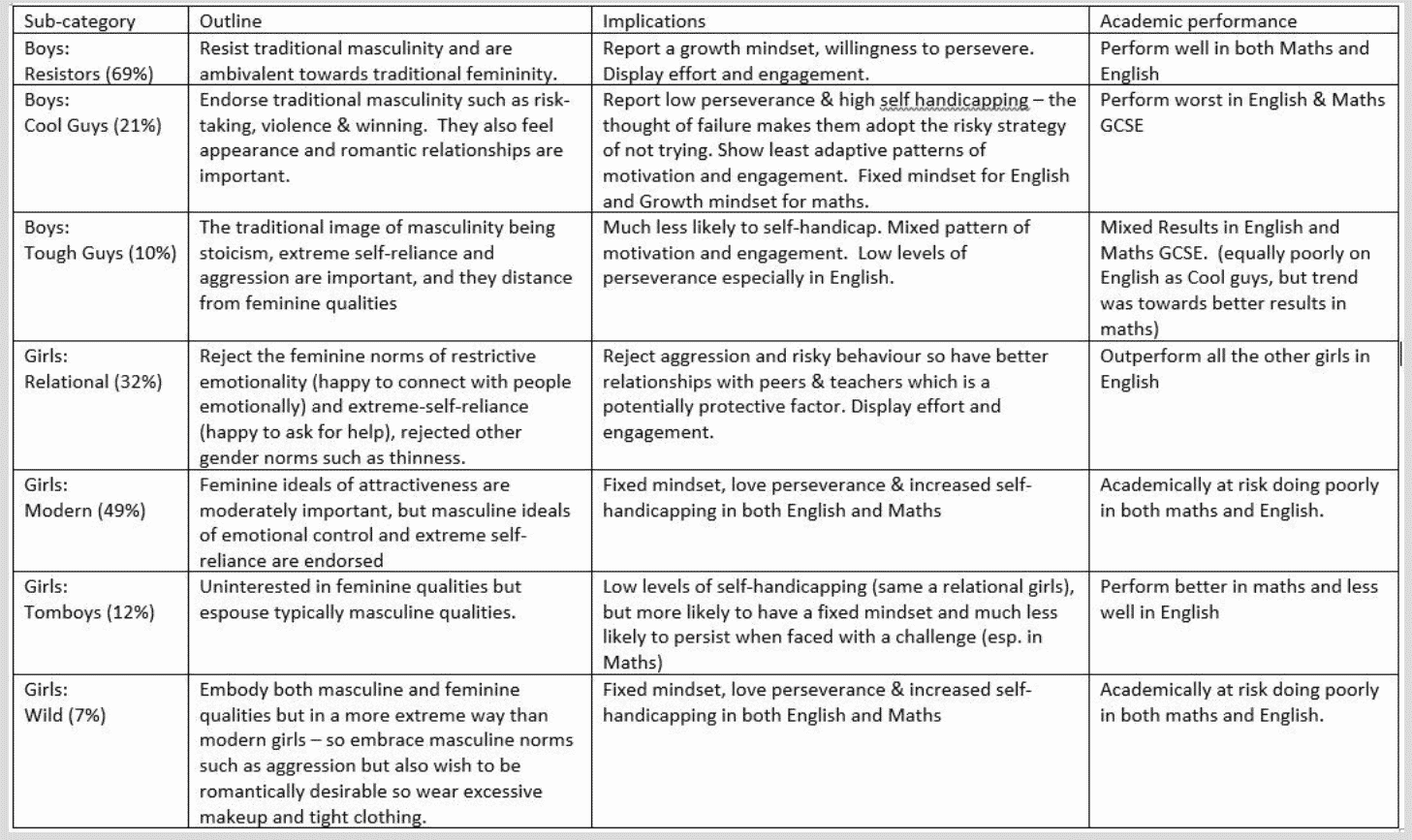

The current study identified 3 sub-categories of boys and 4 subcategories of girls and then considered the implications for their attitude towards school and learning and how that maps onto academic performance in English and Maths GCSE. The findings are summarised in the table below.

The trends we see in girls’ performance can largely be attributed to the success of Relational girls. Both Modern and Wild girls are ‘academically at risk’ and this is over half of the female students in schools (it is worth noting that overall, there is no significant difference in maths performance between the 4 groups of girls), motivation and persistence is higher in Relational girls. Over 2/3 of boys are resistors and so are doing well at school but the other two subcategories are disproportionately skewing the overall results for boys. By lumping girls and boys into distinct groups we miss the nuances of who is succeeding and who is failing at school and our sweeping statements about the diligence of girls means we are failing to support those that may urgently need our help.

What can we do about this?

It has been found that adolescents feel the pressure to conform to gender stereotypes even though they don’t believe them because they overestimate their peers’ support for such norms. As such teachers and schools can start by addressing these false beliefs, highlighting the fact that most people don’t believe in these gender stereotypes and that there is a discrepancy between perceived and actual gender norms. Secondly, we can encourage reliable and trusting friendships which are not contingent on conforming to a specific role, this can provide young people with the social capital to resist gender norms. Finally, we can encourage and teach growth mindset in our classrooms to help break down the beliefs of ‘innate ability’ and ‘self-reliance’.

Note on the research:

This is a really fascinating piece of research and if you really want to understand the nuances, I would highly recommend reading it. The research used a large sample of year 10 & 11 students in the UK, however the sample was not as diverse as it might have been so we need to accept that these results might not reflect the population as a whole and doesn’t consider how cultural beliefs about gender may affect academic performance. It is also worth noting that the results are correlational – they don’t show cause and effect. The proposed mechanisms do suggest that beliefs about gender affect academic performance and not the other way round, however, the authors also acknowledge that there are many other factors which also may be worth exploring such as socio-economic status and culture.

Reference:

Yu, J., McLellan, R. & Winter, L. Which Boys and Which Girls Are Falling Behind? Linking Adolescents’ Gender Role Profiles to Motivation, Engagement, and Achievement. J Youth Adolescence (2020).

Responses