An Introduction to an Inclusive Framework Model for Behaviour Leadership, Management and Discipline

By Bill Rogers, Education Consultant. www.billrogers.com.au

© Dr Bill Rogers, 2020 Intro to inclusive framework behaviour management and discipline (12)

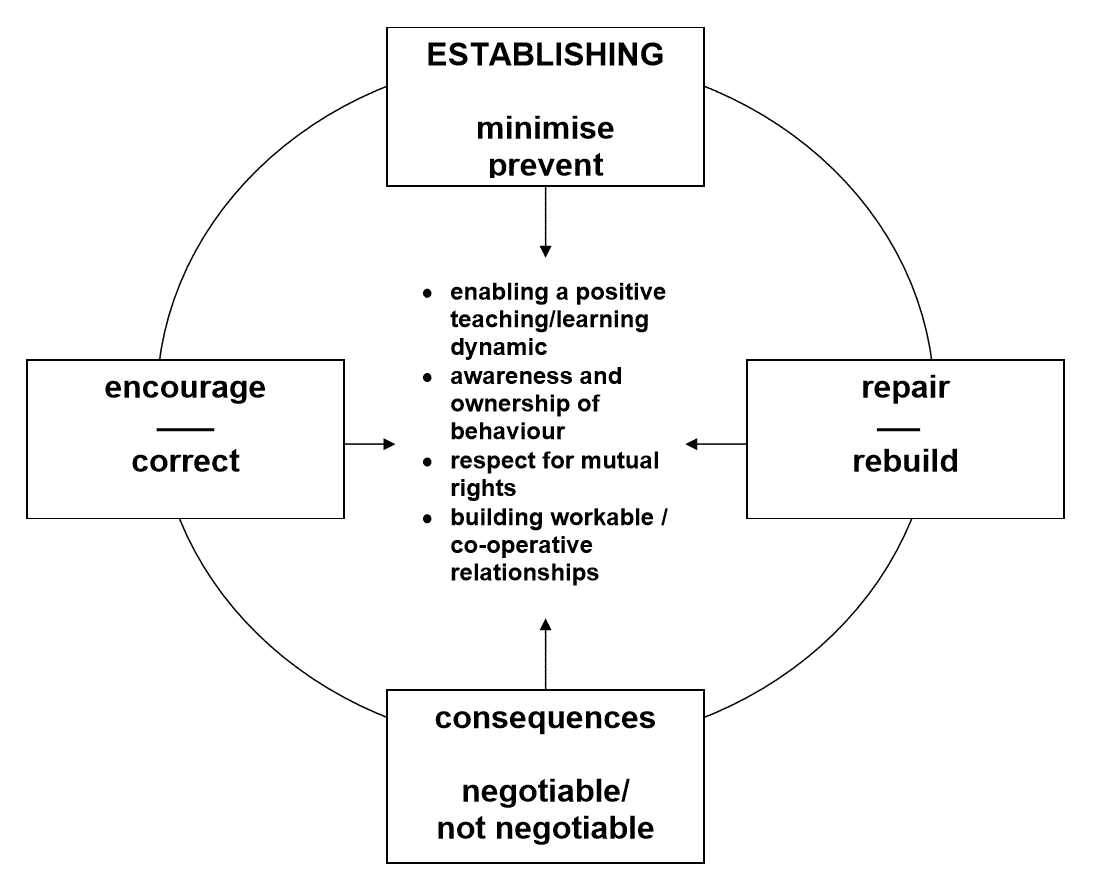

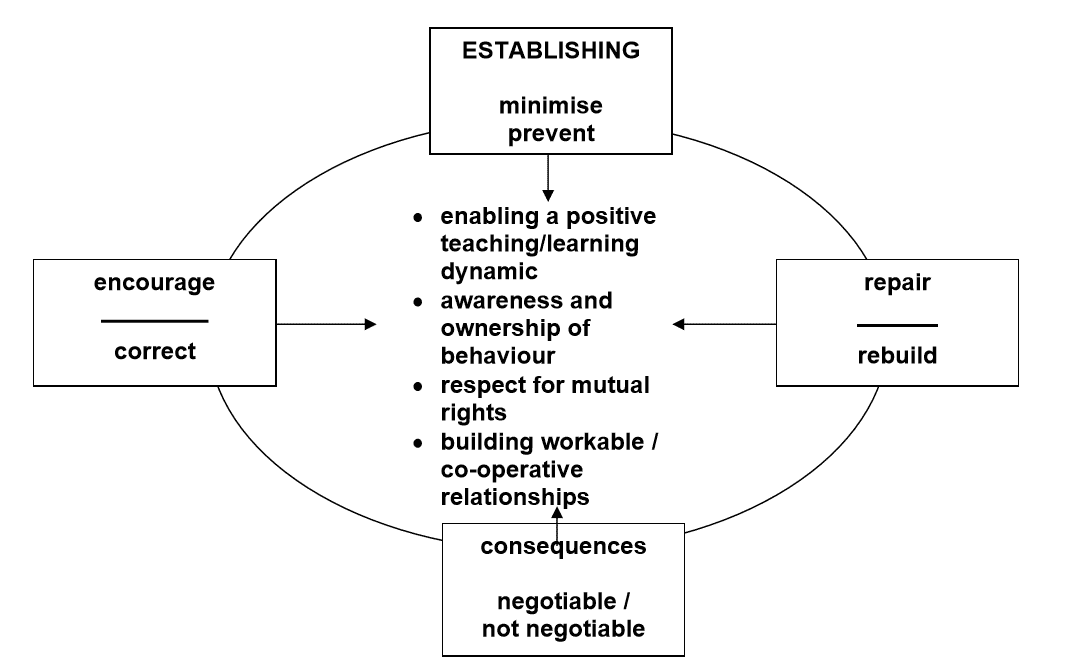

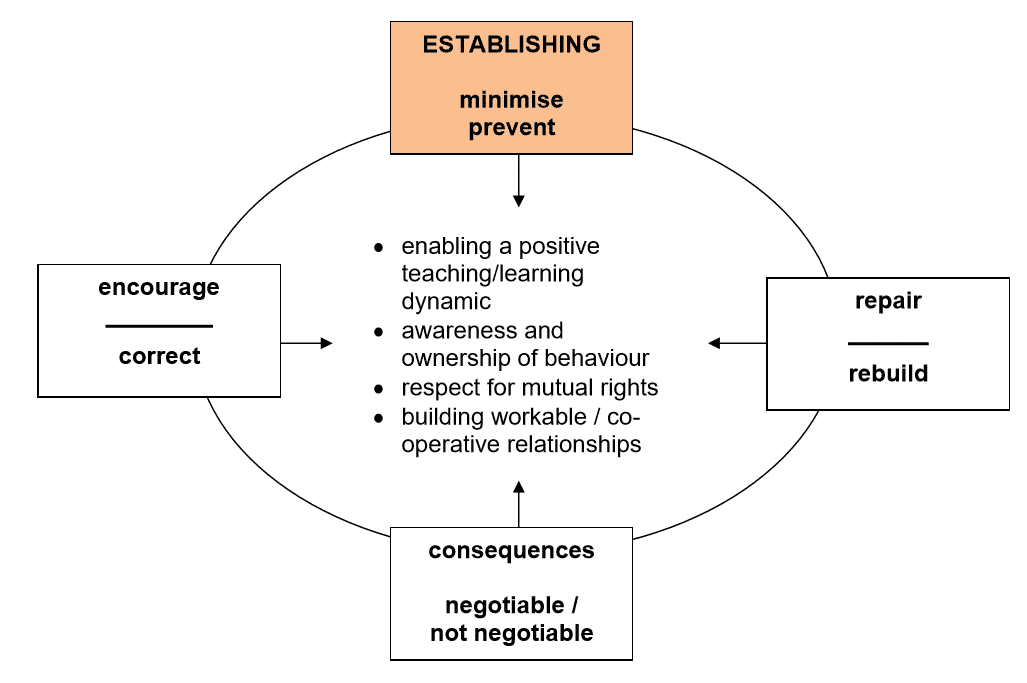

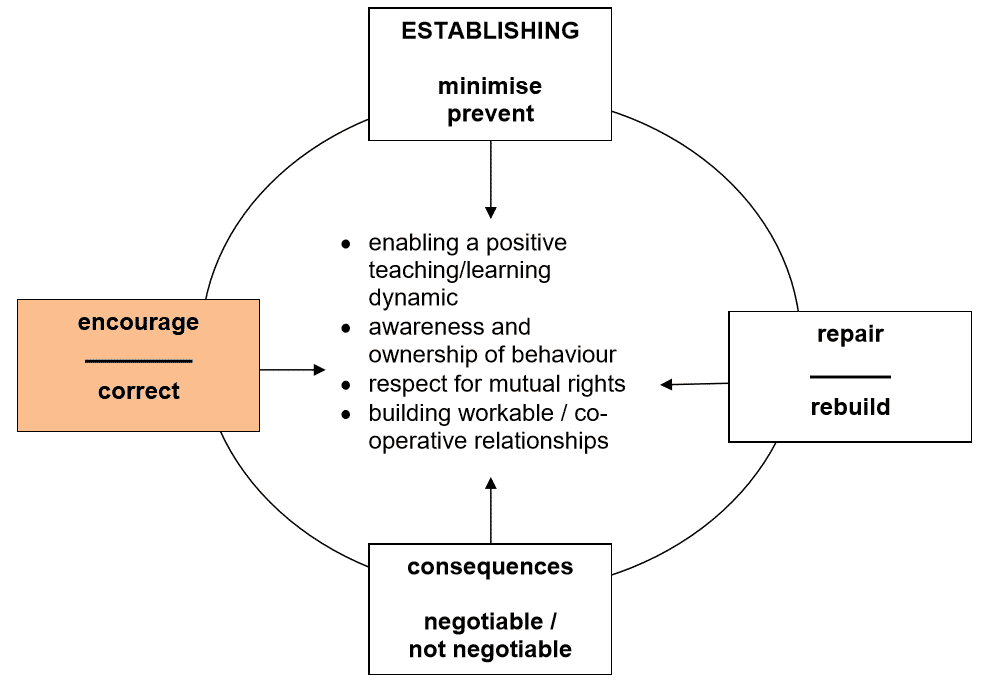

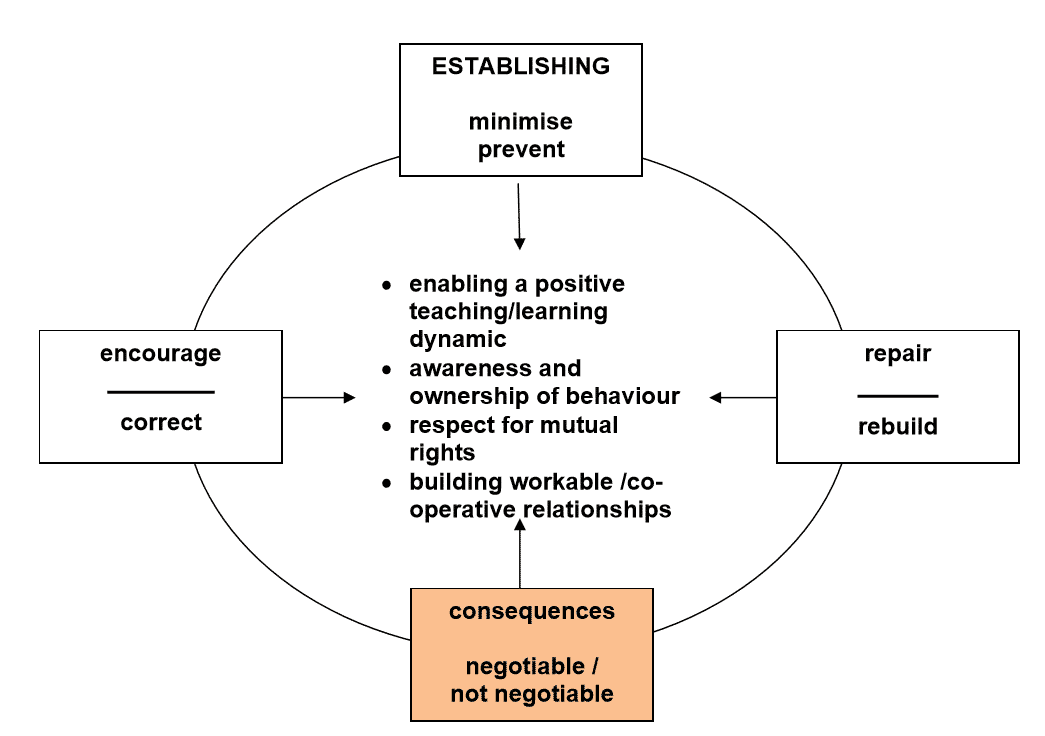

An inclusive model of behaviour management and discipline

Aims of behaviour management

The fundamental aim of all behaviour management and discipline, within any school context, is to enable our students to be aware of their behaviour as it affects others’ rights and to take ownership of their behaviour in regard to the rights of others. These aims also enable positive workable relationships and enable a co-operative teaching and learning dynamic.

When a teacher/leader1 is engaged in any aspect of behaviour management/discipline the over-riding emphasis should focus on the teacher’s motive – and means – and how they enable the student to ‘own their behaviour’. In this sense the authority and adult power (of a teacher) is exercised as ‘power for’ and ‘power with’ their students rather than merely ‘power over’ their students. Of course we need to have ‘authority’ as teacher/leaders but that authority is ‘earned’ by the kind of leadership relationship, and trust, we are able to build and sustain with our students.

To merely claim (or demand) co-operation – or even compliance – from those we lead, teach (and manage) has a very short ‘shelf-life’ and will only lead to unnecessary tension or conflict and work against relational goodwill, trust and the aims noted above.

Relational respect

When engaged in any aspect of behaviour management – particularly discipline – the teacher/leader manages and disciplines towards, and within, a relationship. As the ‘establishing phase’ of a teacher develops – with a class group – they will manage and discipline within and from the relationship they build with their students in those critical first few weeks. Building a workable relationship with a classroom group, and the individuals who form that group, is crucial to the effectiveness of any of the aims noted earlier (p 2). A working relationship with a (class) group and with the individuals is ‘built’ over time. It does not merely occur as a result of our role, our status or our having formal qualifications ‘to teach’ – or even our goodwill. Confident leadership – and any moral authority that can sustain such leadership – is built from one’s knowledge, management skill, communication skill2 and ability to engage, motivate and sustain the student group/s and the individuals in their educational journey. The reciprocal trust, and mutual respect of our students, will develop within that relationship, and is built from such leadership.

Building a co-operative and respectful learning community through our teacher/leadership : the model.

This is an integrated and inclusive model of behaviour management. There are four main ‘entry points’ that denote essential features of our characteristic leadership :- establishment, encouragement/correction, consequences and repairing/rebuilding; each feature and aspect of our leadership depending on the other, (p 2). No one ‘entry point’ stands alone; no one aspect of leadership is enough, by itself. For example, when a teacher is engaged in corrective management or discipline, that correction depends on the teacher having a clear understanding with their class/group about fundamental rights, fair rules and expectations for appropriate behaviour; the ESTABLISHMENT phase. Teachers should also create a normative climate of encouragement to enable purposeful feedback and confidence for their students regarding their learning and co-operation. On some occasions teachers will need to apply behaviour consequences; these too necessitate prior understanding (with our students) of the relationship between established – fair – rules, the mutual rights that are protected by fair rules and what happens when those rules are ignored or flouted and others’ rights are affected by distracting and disruptive behaviour. Respectful teachers go further than application of fair and related consequences, they also seek to repair and rebuild with their students. Repairing and rebuilding involves rebuilding a workable relationship between the teacher and the individuals concerned. It assures the individuals (or group) that no grudges are held; that their teacher does care.

The ‘Establishment Phase’

In any context where a teacher needs to build a leadership relationship with a group, it is crucial to establish a basis for shared behaviour and learning expectations.

In the ‘establishment phase’ of the relationship between teacher and students there is a ‘natural readiness’ (and a heightened expectation) in our students for the teacher to make clear ‘how things will be … here …’ and why (Rogers, 2011, 2006). They expect their teachers to :- clarify rules (and why we have them); the rights that are the fundamental basis for any rules; the basic routines (that enable smooth running of a busy learning community) and the responsibilities that are expected (in ‘our learning community’). The teacher will also discuss the relationship between rights, responsibilities and rules. The teacher will also discuss the nature of behaviour consequences, emphasising that when rules are broken (and rights affected) that there are consequences that follow, and that such consequences entail responsibility and accountability for one’s behaviour.

In an age-related way, the teacher will spend meaningful time in planned dialogue in their first meeting with the class group in establishing a student-behaviour-agreement. A behaviour-agreement outlines the core rights and responsibilities of students and teacher/s regarding:

- the right to feel safe [this includes ‘emotional and psychological safety’ – our feelings and needs – as well as physical safety];

- the right to be treated with fairness and respect [the way we relate to, and treat, each other – courtesy, civility, basic manners, co-operation];

- the right to learn [and how this right is affected by our behaviour eg. : noise level, distracting and interfering behaviour and what – and how – positive, co-operative, behaviours enable that right to be realized / enjoyed];

The process – the discursive process concerning these core rights – between teacher/leader and classroom group is as important as any documented outcome. [The process of developing such an ‘agreement’ is discussed in detail in Rogers, 2011 and 2015; see also – for early years – Rogers and McPherson, 2014].

When establishing any fundamental rules with students, it is important to focus on the key right behind the rule and attenuate the behaviour expectations within that right. Inclusive language emphasises the community/co-operation : ‘we’, ‘us’, ‘our’, ‘all’, ‘everyone’ … Eg : We all have a right to learn. To learn well here we seek to:

- get to class on time,

- have appropriate materials,

- put our hand up (without calling out) to share in our class discussions or ask for teacher support (in on-task learning time); we do this so we all get a ‘fair go’ …

- use partner-voices and co-operative talk during learning time.

We all have a right to respect and to feel safe : to enjoy respect we need to remember that : we all share the same place here, the same reason for being here; we all share the same basic feelings and needs. It is about the way we treat one another here. We use manners (‘please’, ‘thanks’, ‘excuse me’, ‘ask before we borrow …’). We use considerate language (no put-downs, cheap shots, scoring, bullying …).

A discipline plan within our overall behaviour leadership

While a teacher needs to develop these fundamental establishment understandings about rights/rules to support any behaviour management (and discipline), they also need to plan for their necessary behaviour leadership and discipline when students distract and disrupt in classtime. A ‘discipline plan’ is a teacher’s conscious framework of language and ‘strategy’ for managing distracting and disruptive behaviour. This ‘plan’ enables a teacher to consciously address how their behaviour leadership and discipline is more likely to support the aims noted earlier (p 1). A key feature of such a ‘plan’ is how we balance necessary correction with encouragement (see, later, p 8f).

[A framework for such a plan, including key language skills, is developed in detail in Rogers, 2011 and 2015, and for early years Rogers and McPherson, 2014].

Encouragement

Encouragement is crucial both to the tone of classroom life and learning and the relationship between the teacher and class group and the teacher and each individual. The kind of encouragement students receive has a direct bearing on their self-esteem and their ‘learning confidence’.

Encouragement affirms and motivates, it also gives feedback – descriptive feedback to a student’s behaviour and learning. Rather than using global praise (‘brilliant’, ‘fantastic’, ’wonderful!’, ‘marvellous’ …) descriptive encouragement acts as a ‘form’ of feedback. In terms of a student’s work – rather than ‘8 / 10 great work’ a teacher will describe as well as give a ‘mark’ eg “ … that paragraph clearly shows you understand the relationship between …”, (the teacher then notes what/how the student understood, applied, demonstrated such understanding / skills … etc). “That was really supportive, the way you helped Bradley with his maths …” (this to a student who has made a supportive effort to assist a fellow student …). In terms of both a student’s work and their behaviour such ‘feedback’ (where genuine) both encourages and informs as it focuses on the student’s effort, energy , ownership of behaviour … The focus of such encouragement is not merely the teacher’s ‘praise’ but the student’s thoughtfulness, consideration, application, effort that is acknowledged and affirmed. See also notes (Rogers, 2017) on The Language of Encouragement.

Encouragement can also be ‘instructive’ as a form of ‘least-intrusive’ correction in behaviour management eg.: a student is leaning back in his seat a teacher gives a respectful, encouraging non-verbal cue or an encouraging reminder “Jason ( … ) four on the floor thanks.” The teacher adds a non-verbal cue (with a hand indicating sitting in/up …). There are countless examples that could illustrate this fundamental point about encouraging / reminding language. [See Rogers, 2011/2015].

Correction

Corrective management is aimed at keeping any disciplinary focus (for the student/s) directed to the fundamental purpose and aims for a learning community raising behaviour consequences : focus and encouragement to ‘on-task’ learning; ownership of behaviour and respect for mutual rights (p 1). If corrective management and discipline is to be respectful, purposeful and likely to invite student co-operation it needs to be :-

- ‘Least-intrusive’ wherever possible – moving to more intrusive as is really necessary (see later). By keeping the corrective aspect of our discipline leadership ‘least intrusive’ we keep the corrective language (and tone) more positive, less reactive, less confrontational and more co-operatively invitational.

- Use positive corrective language wherever possible. Avoid easy use (or overuse) of ’don’t’, ‘no’, ‘can’t’, ‘shouldn’t’, or unhelpful interrogatives “why?”/ “are you …?!” Eg. : “Don’t call out …”, ”Don’t chew gum …”, “Don’t talk while I’m talking …”, ”Don’t lean back in your chair …”, “No – you can’t go to the toilet – why didn’t you go at recess?” “Why are you calling out …?” “Are you late …?” Instead, eg :- “Hands up thanks” (in contrast to “Don’t call out …”) directs to the fair, expected behaviour. “Facing this way and listening …” (rather than “Don’t talk while I’m teaching.”). Overuse of ‘don’t’ only tells the student what we don’t want … “Remember to …” is a more positive phrasing than “Don’t forget to …”. ‘Why’ questions are rarely helpful in behaviour transactions; more considered questions direct the student to what they should be doing/thinking (re : their behaviour learning) eg : ‘What’, ‘When’, ‘Where’, ‘How’? “What’s our rule for …?” / “What work do you need to be doing now?” These questions, phrased positively and expectantly, enable, and direct, a student’s behaviour awareness. Compare : “Why haven’t you started work?” say, to a teacher noting task avoidance :- “I noticed you haven’t started work (a brief descriptive cue to raise behaviour awareness)– how can I help?” or even, “What do you need to be doing now?” [a more helpful question] – and (again) “How can I help?”. For example : when working with younger children the phrase “When … then” is more invitational than “No you can’t because …” eg : “Yes you can play with the farm animals – when you’ve finished your work and put the pencils away.” This is more invitational than saying, “No you can’t play with … because you haven’t finished your work …” (See Rogers and McPherson, 2014).

If (for example) a student is late, it is pointless asking them “if” they are late, (“Are you late?”) or asking them “why” they are late … It is more effective / co-operative to acknowledge their lateness – briefly. Welcome them to class – indicate / direct to a seat … and then follow-up with the ‘reasons’ for lateness when the class has settled (during on task learning time) and the teacher has a moment for a brief ‘chat’ / or even after class (again – if time). With any corrective language it is not only the utility that is important (ie : does what we say – as correction – work …, or achieve our aims of discipline …). It is also the value of what we say that matters. Is what we say right? Do we have a value basis for what we characteristically say in our behaviour leadership?

Avoid unnecessary confrontation wherever possible (or embarrassment, or sarcastic put-downs, or ‘cheap shots’ – at the student’s expense …) When we need to use appropriate assertion – even assertive anger – we can do so with appropriate emphasis on the student’s behaviour, while keeping fundamental dignity (of the student) intact. We do this when we address the student’s behaviour decisively and assertively (as context necessitates). Eg : “I don’t make comments about your body (or clothing/or sexuality) … I don’t expect you to make comments about mine …” This to an arrogant adolescent making derogatory/sexist comments … Firm, clear, unambiguous and calm. If the student says he was ‘just joking!’ we will reply – assertively – “It’s not a joke – it stops now.” If they continue we will need to exercise a clear directed choice/consequence that may occasion exit from the classroom for time-out. (Rogers, 2011). Time-out is an example of a more intrusive discipline interaction. Such time-out should occur away from the class group and be supervised by a senior colleague. Of course any time-out consequence should be followed up later, by the initiating teacher, with support from a senior teacher wherever necessary. At early years level take-up-time (cool-off-time) can be utilised in the classroom unless the behaviour is overly aggressive. Be aware of the school’s time-out policy; they do vary. Also, whenever we utilise the time-out consequence it is crucial we follow-up (one-to-one) with the student within 24/48 hours to ‘repair/rebuild’.

Focus on the ‘primary’ issue, or behaviour; avoid getting drawn into (or overservicing) a student’s ‘secondary’ behaviours (such as pouting, clicking of tongue, loud sighing, sulky tone(s) of voice, the overdone frown, raising of eyes, marginal eye contact, their sulky ‘last word’). They may also come from tiredness or frustration; even bad-day … They may related to a student’s behaviour disorder. They occur, most commonly, in a peer audience setting. In a classroom context such ‘secondary behaviours’ are (often) a form of attentional behaviour (a ‘behavioural last word’). There are skills that can enable a teacher to more purposefully keep the management focus directed to the ‘primary / behaviour issue’ regarding student behaviour such as :- tactical ignoring, ‘blocking language’; ‘partial agreement’; refocusing to the rule, or right; affected by a student’s behaviour. Eg. : a student is chewing gum during on-task learning time. The teacher directs the student to put it in the bin (with an incidental direction) “The bin’s over there Sean, thanks …”. If the student engages in ‘secondary behaviours’ – such as sighing and saying, “Other teachers don’t care if we chew gum” – the teacher will ‘partially agree’. “I can’t answer for other teachers. The school rule is clear in our class … the bin’s over there. Thanks.” The teacher will (then tactically ignore the student’s indulgent sigh, the frown, the raised eyes …Or they might simply say, “You know the rule … the bin’s over there.” As a clear re-direction (‘blocking’ the whinging sigh). Of course our tone of voice and manner will indicate how positive and ‘expectant’ we are about student co-operation (even on a small ‘behaviour issue’ such as this!). The teacher will – then – give the student ‘take-uptime’ (Rogers, 2011) by ‘moving away’, leaving ownership / and expectation / and some ‘grace’ with the student. If such behaviour occurs several times in a lesson the teacher will follow-up with the student later – away from their peer audience (after class) to enable the student to be aware of how their behaviour ‘comes across’ in classtime, and how it affects others (including the teacher) (see later). Where a student displays any frequent ‘secondary behaviours’ this will need to be followed up one-to-one with the student in non-class time.

Another typical example : It is whole-class teaching time. As the teacher is explaining the topic under discussion, two students are busily chatting (seemingly ignoring him). The teacher pauses, he cues the class “Excuse me everyone …” (This – briefly – to the class). He then directs his gaze to the two students, “Chrissy ( … ) Brooke ( … ) you’re chatting.” [This brief description raises their attention, their behaviour awareness, and some cognitive take-up …] He adds, “It’s whole-class teaching time”. [Another brief descriptive cue]. At this point the teacher refocuses his attention back to the whole class resuming the flow of whole-class teaching. He has been brief, positive, respectful … conveying expectation. By turning his direction, and attention, from the distracting students, ‘away’ (as it were) after having given the students in question a descriptive cue, he gives take-up time conveying expectation of co-operation (or, at least, compliance). The ‘turning away’ also demonstrates the teacher’s conscious refocusing of attention to the rest of the class.

As the teacher resumes the flow of whole-class teaching (after the brief correction …) Chrissy lets out an indulgent sigh (he tactically ignores this). Brooke adds a sulky mutter, “We’re only talking about the work!” She presents with a sulky pout, arms folded. The teacher briefly refocuses “Even if you’re talking about the work …” [partial agreement] “it’s whole-class teaching time” [another brief descriptive cue]. “You need to be facing this way and listening, thanks” [a brief, simple direction]. He tactically ignores her attentionally sulky demeanour (her raised eyes-to-ceiling and over-done frown …). He, again, gives take-up-time (to the two students), and resumes the flow of the lesson back to the whole-class. This discipline issue has been addressed least-intrusively, respectfully, and reasonably briefly without overservicing the students’ ‘secondary’ behaviours. If the teacher thinks it is necessary he will have a brief, after-class chat with the students about their ‘secondary behaviours’ (away from the peer audience).

Some ‘secondary behaviours’ obviously need to be briefly and firmly, addressed and refocused quickly :- where students’ loud mutterings, or gestures are overtly rude, repeatedly disruptive, in any way hostile, sexist, racist, or their behaviour is in any way potentially dangerous (see earlier example of assertive language). If, for example, a student responds to a teacher’s direction with an overtly disrespectful tone and word it will be enough (at this point) to say, “I don’t speak to you disrespectfully (use an age-appropriate word) I don’t expect you to speak to me that way.” This is said (addressing the ‘secondary behaviour’) respectfully, calmly and firmly. The teacher will then refocus the student to the direction or reminder at issue. In such cases the student will (often) sulkily comply (with frown, sigh …). If the student continues to be disruptive we will need to make the consequences (immediate or deferred) clear. We do this calmly, respectfully, clearly. This ‘secondary behaviour’ can be tactically ignored to avoid unnecessarily ‘feeding’ the behaviour exchange at this point.

Our ‘natural’ response to may be to exert our power to challenge, confront or argue. Tactical ignoring is a context dependent skill.

The approach noted above, though, keeps the discipline transaction ‘leastintrusive’, where possible, positive and relationally co-operative. There is – of course – conscious skill inherent in any such discipline transactions (even in these few examples). These skills are discussed in detail – with a wide range of actual case examples across a range of student ages and behaviours – in Rogers (2011), (2015) and Rogers and McPherson (2014).

Re-establish the working relationship with the student/s after correction – even in the course of a busy lesson. This can be as basic as re-establishing a positive tone / manner (after correction), as we ‘re-visit’ a student’s desk / workspace to focus on their work (showing ‘no grudges’ are held …). Balancing encouragement – beyond any necessary correction – is crucial in behaviour management and motivation; children need to hear more of the second than the first (see later).

Keep the fundamental respect intact; this is axiomatic. We avoid any sarcasm, mean-spirited comments, flippant comments; any put-downs – (tempting though it may be at times).

Follow-up, follow-through, with a student/s beyond the immediate, classroom, context on issues that matter. It is crucial to follow-up (beyond class time) to reemphasise, or discuss, a concern about behaviour or learning with a student who has been disruptive (in classtime), or to direct a student to an appropriate task (‘finishing work’*; cleaning up mess not cleaned up in work time; or the organising of ‘detentions’ where appropriate). The protocols of any follow-up include : briefly tuning in to how a student feels; emphasising concerns about their behaviour or their struggle with classwork (we do not verbally, or emotionally, engage in any psychological ‘pay back’ – tempting as that might be …); giving an appropriate right of reply to the student/s and refocusing to the behaviour in question by reference to the student-behaviour-agreement** (the basic rights/rules/relationship affected by their behaviour) and working with the student on necessary change and support in the future. Always finish any consequential follow-up as amicably as possible, (even in the brief after-class chats). (See the notes on ‘The Establishment Phase’ 2019)

* Finishing work’ as an after-class needs careful thought. It is not always an appropriate behaviour consequence particularly for students with significant learning concerns or for students who are seeking power exchanges. (See Rogers, 2011). ** A student behaviour agreement is a common usage term used to denote the rights/rules/responsibilities concerning behaviour in a school/classroom context. It is discussed with the class group and published on user-friendly wall posters, in school diaries (at secondary level) or in a published take-home agreement. (See Rogers 2011, and Rogers and McPherson 2014).

Behaviour Consequences

As noted before, each of these ‘entry points’ delineates aspects of our teacher leadership that enable a purposeful, positive and co-operative learning community. Each ‘entry point’ also enables the other entry points. All ‘entry-points’ – as described within this model – enable the core aims of management and discipline. No one ‘entry point’ stands in isolation; each builds on, supports and needs the other ‘entry points’ to enable and support that which we aim for with our students (see aims p 1).

Behaviour consequences can be ‘negotiable’ where appropriate; some consequences, of course, will be non-negotiable. ‘Negotiable consequences’ are those where the teacher works one-to-one (in non-class time) with the student utilising questions such as : ‘What happened …?’; ‘What rule/right was affected by your behaviour?’; ‘What’s your side of the story?’ (a right-of-reply question); ‘What can you do to fix things up / improve things?’; ‘How can I help?’. These can also be used in written proformas such as in a detention or during a time-out consequence or in a pre-mediation meeting. We only do this if the student is calm enough. If the student struggles with their writing the supervising teacher will record their responses for them.

‘Non-negotiable’ consequences are occasioned in situations where a student is repeatedly disruptive, threatening, hostile or aggressive; or engaging in unsafe/dangerous behaviours such as bullying or verbal/physical violence, or using drugs on school premises … (timeout is a typical non-negotiable consequence as is internal/external suspension).

Students need to know that rights-disturbing and rights-denying behaviour will always occasion such consequences.

Behaviour consequences are essentially the teacher/leader seeking to enable (even teach) responsibility and accountability by linking inappropriate, disruptive and wrong behaviour(s) with appropriate and fair consequences. In this sense a consequence is not primarily (or merely) a punishment (although students may often see them in that way).

- Behaviour consequences are related to the affected (and established) rights and rules as much as possible.

- Behaviour consequences may be immediate (depending on behaviour audience and context (eg : time-out), or deferred until a later time (eg : ‘after class chat’; behaviour interview; informal/formal detention; restitutional consequence …). Eg : If a student chooses (refuses) not to put their smart phone away in class time the teacher would make the consequence clear. “If you choose not to put the phone away, I’ll have to follow this up in your own time.” (The deferred consequence). We don’t simply take the phone away in the first instance (of noticing its use by a student). We give a clear rule reminder and a directed choice (no choices, as such, are ‘free’). “The rule is clear. I expect you to put your phone away on my desk (till the end of the lesson) or “Your phone needs to be off and in your bag.” We do not brook discussion or argument; we give some take-up time. If the phone is still not turned off and put away then the teacher will carry through the consequence stated (the deferred consequence). [The same consequential process would occur in schools with a confiscation policy (where students refuse to ‘hand over’ their phone on receipt of respectful teacher direction)].

- Some behaviour consequences can be ‘negotiated’ with the student at a calmer time, (often ‘after class time’) – see key questions noted earlier.

- There is often a ‘primary’ and a ‘secondary’ aspect to behaviour consequences as when a teacher engages in ‘repairing’ and ‘rebuilding’ after a ‘time-out’ episode.

- Behaviour consequences for more serious behaviours (aggressive/threatening behaviours, unsafe behaviours, bullying) should be known in advance; in this sense such consequences are non-negotiable (see earlier).

- Behaviour consequences are never merely an end in themselves – caring and supportive teacher/leaders ensure that repairing and rebuilding are part of the consequential due process. In this way students are more likely to learn something constructive from behaviour consequences.

- The fair, respectful certainty of the consequences is much more effective (as a learning experience for the student) than the severity of consequences (as when some teachers lecture or hector a student when applying a consequence). Let the consequence do the ‘teaching’.

[How these features of consequences are developed is explained in case study approaches in Rogers : 2011 and 2015, and Rogers and McPherson, 2014].

Repairing and Rebuilding

As noted earlier, repairing and rebuilding are essential features of a teacher’s management and discipline. For example if a teacher has had to discipline a student for being ‘out of their seat’ – unnecessarily and distracting others – during on-task learning time or for being ‘too loud’, or repeatedly calling out, or for silly (and possibly) dangerous seat-leaning or inappropriate language (whatever …) – at a later stage in the lesson the teacher will re-establish a working relationship with the student. This can be as basic as going back to their desk / work area and asking how they are going, or giving feedback about their work. This communicates a fundamental message that no grudges are held (beyond the earlier, teacher correction). It also communicates that we care and the relationship is not adversely affected between the adult to student.

Other aspects of repairing / rebuilding include after-class ‘chats’; informal counselling; developing individual-behaviour / learning plans with the student*, mediation and restitution opportunities – even whole-class meetings to raise issues of common concern with the wider student group.

When we take time, effort and goodwill to repair and rebuild relationships with our students, and between our students we re-engage hope, relational goodwill and trust. Repairing and rebuilding also re-establishes; this ‘entry point’ becomes – in a sense – ‘preventative’. Above all it affirms that fundamental humanity that is at the heart of our profession.

Key references

ROGERS, B. (2006) Cracking the Hard Class : Strategies For Managing the Harder Than Average Class Sydney : Scholastic. [Sage Publications : London].

ROGERS, B. (2015) Classroom Behaviour : A practical guide to effective teaching, behaviour management and colleague support. (4th Edition) Sage Publications : London.

ROGERS, B. (2011) You Know the Fair Rule and Much More, Australian Council for Educational Research Press : Melbourne Third Edition [London : Pearson Education] (Second Edition).

ROGERS, B. and MCPHERSON, E. (2014) Critical First Steps : Behaviour Management in the Early Years Curriculum Corporation : Melbourne. (In the UK published by Sage Publications : London (2008) Behaviour Management With Young Children : Crucial First Steps With Children 3 – 7 Years.

Indepth,straight to the point and broken down for all to understanding, and I really loved the examples given, and the do’s and don’ts in classroom.